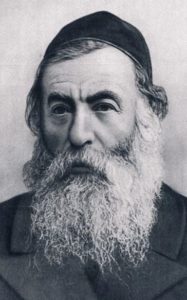

Father of Religious Zionism

Yitzchak Yaacov Reines (1839-1915) was born near what is now Pinsk, Belarus to a long line of rabbis. He studied at the famous Volozhin Yeshiva where he received his rabbinic ordination in 1867. Rabbi Reines became the rabbi of the town of Svintsyan, Lithuania, just north of Vilnius. There, he opened his own yeshiva which, for the first time, included a secular studies curriculum as well. In 1882, a large assembly of rabbis gathered in St. Petersburg to discuss easing the plight of Russian Jewry, then suffering immense persecution and poverty. Reines proposed spreading his successful yeshiva model across Russia, allowing Jews to integrate into mainstream society (and economy) without abandoning their faith and traditions. The assembly rejected his plan, so Reines continued his mission on his own. His Svintsyan Yeshiva created a ten-year program that would give students both rabbinic ordination and a government-approved job. Unfortunately, the yeshiva faced too much opposition and shut down after four years. Meanwhile, Rabbi Reines was an active member of Hovevei Zion. In 1893, together with Rabbi Shmuel Mohilever, he proposed that Jews settle in their ancestral Holy Land and organize a mercaz ruhani, “spiritual centre”, that would combine Torah with good-old-fashioned agricultural labour. In 1899, Reines participated in the Third Zionist Congress, following which he kept a regular correspondence with Theodor Herzl. Rabbi Reines worked tirelessly to get more approval and understanding for the Zionist movement among traditional and Ultra-Orthodox Jews. In 1901, he built on his earlier mercaz ruhani model to start a new “religious Zionist” movement, known as Mizrachi. That same year, at the Fifth Zionist Congress, Reines played an instrumental role in preventing Zionism from becoming entirely secular and anti-religious (stopping the radical “Swiss faction” behind it). In 1902, Rabbi Reines published A New Light on Zion, a book that addressed the concerns that Ultra-Orthodox Jews had with Zionism. In it, he debunked many of the myths surrounding Zionism, and also composed a manual for establishing a model Jewish state in Israel that would be both materially and spiritually prosperous. Rabbi Reines assembled a large gathering of rabbis in Vilnius in 1902 to officially launch the religious Zionist movement. It would later gave birth to Israel’s first religious political party, the Mizrachi Party, which established Israel’s Ministry of Religious Affairs, and made sure that the Israeli government would adhere to Sabbath and kashrut observance. Mizrachi also built Israel’s first network of religious schools (which are Zionist and encourage students to serve in the IDF). The youth movement of Mizrachi, called Bnei Akiva, is the largest Jewish youth organization in the world (with 125,000 members in 42 countries) and operates religious Zionist schools around the globe. In 1905, Rabbi Reines resurrected his old vision and opened a new yeshiva in Lida, near Minsk, Belarus, which integrated religious and secular studies. Rabbi Reines also came up with a new Talmud-study system, wrote a commentary on the Midrash, and published a number of other acclaimed books. Today, the religious Zionist movement that he founded remains one of the largest and most influential in Israel. Rabbi Reines’ yahrzeit is this Sunday.

Yitzchak Yaacov Reines (1839-1915) was born near what is now Pinsk, Belarus to a long line of rabbis. He studied at the famous Volozhin Yeshiva where he received his rabbinic ordination in 1867. Rabbi Reines became the rabbi of the town of Svintsyan, Lithuania, just north of Vilnius. There, he opened his own yeshiva which, for the first time, included a secular studies curriculum as well. In 1882, a large assembly of rabbis gathered in St. Petersburg to discuss easing the plight of Russian Jewry, then suffering immense persecution and poverty. Reines proposed spreading his successful yeshiva model across Russia, allowing Jews to integrate into mainstream society (and economy) without abandoning their faith and traditions. The assembly rejected his plan, so Reines continued his mission on his own. His Svintsyan Yeshiva created a ten-year program that would give students both rabbinic ordination and a government-approved job. Unfortunately, the yeshiva faced too much opposition and shut down after four years. Meanwhile, Rabbi Reines was an active member of Hovevei Zion. In 1893, together with Rabbi Shmuel Mohilever, he proposed that Jews settle in their ancestral Holy Land and organize a mercaz ruhani, “spiritual centre”, that would combine Torah with good-old-fashioned agricultural labour. In 1899, Reines participated in the Third Zionist Congress, following which he kept a regular correspondence with Theodor Herzl. Rabbi Reines worked tirelessly to get more approval and understanding for the Zionist movement among traditional and Ultra-Orthodox Jews. In 1901, he built on his earlier mercaz ruhani model to start a new “religious Zionist” movement, known as Mizrachi. That same year, at the Fifth Zionist Congress, Reines played an instrumental role in preventing Zionism from becoming entirely secular and anti-religious (stopping the radical “Swiss faction” behind it). In 1902, Rabbi Reines published A New Light on Zion, a book that addressed the concerns that Ultra-Orthodox Jews had with Zionism. In it, he debunked many of the myths surrounding Zionism, and also composed a manual for establishing a model Jewish state in Israel that would be both materially and spiritually prosperous. Rabbi Reines assembled a large gathering of rabbis in Vilnius in 1902 to officially launch the religious Zionist movement. It would later gave birth to Israel’s first religious political party, the Mizrachi Party, which established Israel’s Ministry of Religious Affairs, and made sure that the Israeli government would adhere to Sabbath and kashrut observance. Mizrachi also built Israel’s first network of religious schools (which are Zionist and encourage students to serve in the IDF). The youth movement of Mizrachi, called Bnei Akiva, is the largest Jewish youth organization in the world (with 125,000 members in 42 countries) and operates religious Zionist schools around the globe. In 1905, Rabbi Reines resurrected his old vision and opened a new yeshiva in Lida, near Minsk, Belarus, which integrated religious and secular studies. Rabbi Reines also came up with a new Talmud-study system, wrote a commentary on the Midrash, and published a number of other acclaimed books. Today, the religious Zionist movement that he founded remains one of the largest and most influential in Israel. Rabbi Reines’ yahrzeit is this Sunday.

Words of the Week

I really wish the Jews again in Judea an independent nation.

– John Adams, second president of the United States

Mordechai Martin Buber (1878-1965) was born in Vienna to a religious Jewish family. His parents got divorced when he was just three years old, so Buber was raised in what was then Poland by his grandfather. Despite growing up in a richly Hasidic home, Buber began reading secular literature and returned to Vienna as a young man to study philosophy. Around the same time, he became active in the Zionist movement and soon became the editor of Die Welt, the main newspaper of Zionism. It wasn’t long before Buber became dissatisfied with the secularism and “busyness” of Zionism and returned (partially) to his Hasidic roots. He saw in Hasidic communities the right model for a new Israel, and a better alternative to the entirely-secular kibbutz. Buber ultimately saw Zionism not as a nationalist or political movement, but as a religious movement that should, first and foremost, serve to spiritually enrich the Jewish people—along with the rest of the world. He would later be credited with being the father of “Hebrew humanism” and “spiritual Zionism”. In 1908, he was invited to address a group of Jewish intellectuals known as the “Prague Circle”, and to “remind them about their Judaism”, as the group’s leader had requested. Among the members of the Circle was (former Jew of the Week)

Mordechai Martin Buber (1878-1965) was born in Vienna to a religious Jewish family. His parents got divorced when he was just three years old, so Buber was raised in what was then Poland by his grandfather. Despite growing up in a richly Hasidic home, Buber began reading secular literature and returned to Vienna as a young man to study philosophy. Around the same time, he became active in the Zionist movement and soon became the editor of Die Welt, the main newspaper of Zionism. It wasn’t long before Buber became dissatisfied with the secularism and “busyness” of Zionism and returned (partially) to his Hasidic roots. He saw in Hasidic communities the right model for a new Israel, and a better alternative to the entirely-secular kibbutz. Buber ultimately saw Zionism not as a nationalist or political movement, but as a religious movement that should, first and foremost, serve to spiritually enrich the Jewish people—along with the rest of the world. He would later be credited with being the father of “Hebrew humanism” and “spiritual Zionism”. In 1908, he was invited to address a group of Jewish intellectuals known as the “Prague Circle”, and to “remind them about their Judaism”, as the group’s leader had requested. Among the members of the Circle was (former Jew of the Week)