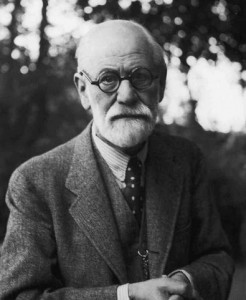

Israel’s “Spiritual” Founding Father

Theodor Herzl

Theodor Binyamin Ze’ev Herzl (1860-1904) was born in what is now Budapest, Hungary to Ashkenazi Jewish parents with mixed Sephardic heritage. He was a descendant of the great Spanish rabbi and kabbalist Yosef Taitazak. Herzl first wished to be a scientist and engineer, then switched to law and journalism. In his youth, he was ashamed of the many impoverished and uneducated Jews in Hungary, and was inspired by the Germans whom he felt were the most civilized and cultured of peoples. During his time at the University of Vienna, he was a member of a German nationalist club, but left because of their rampant anti-Semitism. After a brief law career, Herzl became a journalist for a Viennese paper. In 1894, he was sent to cover the Dreyfus Affair where a French-Jewish military officer was falsely accused of treason by anti-Semites, and heard the masses chant “Death to the Jews”. While this is often cited as the moment that awoke him to the plight of the Jews, a more likely factor was what happened at the same time back home in Vienna. The virulently anti-Semitic Kart Lueger was elected mayor – this was the man whom Hitler would later credit as being his major inspiration. Although Herzl once believed that Jews should assimilate and become Germans, he soon realized that the Germans were not as civilized as he thought, and that the Jew would never be accepted in European society. Immersing himself in Jewish and early Zionist literature (especially the work of the great Sephardic rabbi and mystic Yehuda Alkali), he came to understand that the only solution for the Jews was not to abandon their heritage, but to embrace it forcefully and return to their Promised Land (or some other land if that didn’t work). He wrote: “Zionism is first and foremost a return to Judaism.”

Herzl got to work and drafted Der Judenstaat, his manual for “The Jewish State”. It was published in early 1896 and quickly became a bestseller. Meanwhile, Herzl succeeded in arranging a meeting with the German emperor, injecting a huge boost of credibility to his campaign. The following month, Der Judenstaat was published in English, and a month after that Herzl met with the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire, who awarded him a medal. Herzl continued traveling, speaking, and meeting with dignitaries and Jewish communities. In 1897 he spent much of his own savings to found a Zionist newspaper and to organize the First Zionist Congress, where he was elected its president. It should be noted that Herzl had many opponents, including assimilated Western European Jews, those that had entered the European nobility, most of the wealthy Jews and bankers who lived in Europe comfortably, as well as the Ultra-Orthodox Jews who distrusted his secular leadership. Nonetheless, he charged onwards, believing that “The Jews who wish for a State will have it.” Herzl continued negotiating with the British, the Turks, and the Russians. He traveled to Israel for the first time in 1898, and once more met the German emperor there for discussions. He also traveled to Russia to try to ease the plight of the Jews and end the pogroms. Meanwhile, he worked on a novel to describe his vision more romantically, and published Altneuland in 1902, which also became a bestseller. When translated into Hebrew by Nahum Sokolow, he chose to title the book Tel Aviv, based on a verse from the Tanakh (Ezekiel 3:15). The name would, of course, later be adopted for Israel’s largest city. Herzl met with the Pope in early 1904, famously refusing to kneel before him or kiss his hand as was required. The Pope refused to help the Jews unless they all converted to Christianity, which Herzl quickly rejected. The meeting lasted less than a half hour. (The next Pope would reverse the Church’s position in 1917 and support the Zionist cause.) Herzl had been battling a heart condition for quite a while, and unfortunately succumbed to it in the summer of 1904. He didn’t live to see his dream fulfilled, but on the 5th of Iyar in 1948, the State of Israel became a reality, with David Ben-Gurion proclaiming the rebirth of an independent Jewish state in the Holy Land, with a portrait of Herzl behind him. The city of Herzliya in Israel is named after him, and the 10th of Iyar (next Wednesday), is a minor holiday in Israel called Herzl Day. Happy Yom Ha’Atzmaut!

Words of the Week

…I believe that a wondrous generation of Jews will spring into existence. The Maccabees will rise again… We shall live at last as free men on our own soil, and die peacefully in our own homes. The world will be freed by our liberty, enriched by our wealth, magnified by our greatness. And whatever we attempt there to accomplish for our own welfare, will react powerfully and beneficially for the good of humanity.

– Theodor Herzl, Der Judenstaat

The eldest son of

The eldest son of