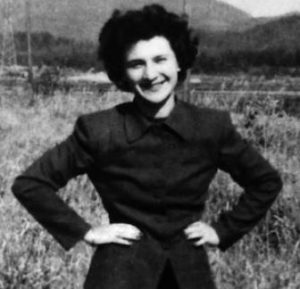

Israel’s First Commando

Yitzhak Sadeh

Izaak Landoberg (1890-1952) was born to a religious Jewish-Polish family in Lublin, then part of the Russian Empire. He was a student of Rabbi Hillel Zeitlin in his youth, but drifted towards secularism as a young adult. An avid athlete, Landoberg particularly enjoyed wrestling, and was once crowned St. Petersburg’s wrestling champion. When World War I broke out he joined the Russian Army and fought valiantly, receiving a medal. During this time, he met Joseph Trumpeldor and became a Zionist. He helped Trumpeldor establish the HeHalutz movement, which trained young Jews in agricultural work to settle the Holy Land. In 1920, he made aliyah and changed his last name to Sadeh, “field”. He joined the Haganah, and co-founded Gdud HaAvoda, the Labor and Defense Battalion, along with 80 others who worked tirelessly to drain swamps, pave roads, plant farms, defend Jewish settlements, and build kibbutzim. Sadeh defended the Jewish residents of Haifa and surrounding towns during an Arab uprising in 1929, and again during the Arab riots between 1936-1939 as the commander of the Jewish Settlement Police. It was during this time that he created two new fighting units. The first was Nodedet, a troop unit that started going on the offensive instead of always being on the defence from Arab violence. The second was Plugot Sadeh, “Field Companies”, the Haganah’s commandos, the first Jewish elite strike force. This evolved into the Palmach in 1941, which Sadeh commanded until 1945. At that point, he was made Chief of Staff of the Haganah, and set the foundations for the future IDF, crafting its first protocols, structures, and training procedures. Sadeh played an instrumental role during the War of Independence, commanding several brigades and creating Israel’s first armoured (tank) brigade, too. Sadeh retired at the war’s end with the rank of major general, and went on to have a successful literary career, publishing a variety of books, essays, and plays. Today there is a Yitzhak Sadeh Prize for Military Literature given in his honour, as well as several kibbutzim and many streets named after him in Israel. There is also a “Yitzhak Sadeh Wandering Song Club” with hundreds of members (mostly soldiers) that gather over bonfires, food, Israeli folk songs, and Sadeh’s wise words, seeing in Sadeh their spiritual mentor. Sadeh is recognized as one of the “fathers of the IDF”. This friday is his yahrzeit.

14 Tefillin Facts Every Jew Should Know

The Significance of Judaism’s Four Holy Cities

Words of the Week

If I am to understand that you are inquiring whether I am of Jewish origin, I can only reply that I regret that I appear to have no ancestors of that gifted people.

– J.R.R. Tolkien