The Military Genius Who Made War—and Peace

Moshe Dayan (1915-1981) was born on the first kibbutz, Degania Alef, to Jewish-Ukrainian parents. He was named after Moshe Barsky, a kibbutznik from Degania who was murdered in an Arab attack. At just 14 years of age, Dayan joined the Haganah defense force. In 1936, he began training with a British military unit headed by his hero, Major General Wingate. During World War II, Dayan was part of a unit that ran covert operations in Nazi-allied Vichy French territory and participated in the Allied invasion of Syria and Lebanon. In one battle, a sniper bullet missed his head, but the resulting shrapnel destroyed his left eye. His eye muscles were ruined, too, so he could not be fitted with a glass eye, and henceforth wore his characteristic black patch. During Israel’s Independence War, Dayan commanded the Jordan Valley units, and was able to stop the Syrian advance. He also led the takeover of towns like Ramle and Lod, and was part of the negotiating team that brought the war to an end. In 1949, Dayan took charge of the Southern Command and worked to secure Israel’s borders. This meant a policy of strong retaliation for Arab attacks, at times brutal. While it brought him a lot of condemnation, Dayan insisted that it was “the only method that proved effective”. In 1953, Ben-Gurion appointed Dayan the new Chief of Staff, and the latter went on to implement Ben-Gurion’s “three-year defence programme” to reorganize the IDF. Among his accomplishments was founding a military academy for high-ranking officers and establishing new intelligence units. In 1955, Dayan and Shimon Peres signed a series of deals with France to strengthen the IDF, leading to the purchase of over 100 jets, 260 tanks, and 300 trucks. In 1956, Dayan led Israel’s operation in the Sinai (jointly with France and England) and proved his military genius. The French later awarded Dayan with a Legion of Honour. After retiring from the IDF, Dayan joined Ben-Gurion’s government as Minister of Agriculture. During the Six-Day War, he took the military reins again as defense minister and oversaw the liberation of Jerusalem. He remained defense minister until the Yom Kippur War, after which he resigned due to what is generally considered to be his greatest failure. He subsequently fell into a deep depression. In 1977, Dayan returned to government as foreign minister and, no longer the hawk he once was, played a key role in the peace treaty with Egypt. Dayan spoke Arabic fluently, and lamented that more Israelis didn’t. He wrote four books and was also an amateur archaeologist, amassing a large collection of antiques which are now at the Israel Museum. In 1981, he founded a new political party, Telem, but passed away shortly after from a heart attack and complications of cancer. The New York Times eulogized him as “a general who made war, a diplomat who made peace.”

Moshe Dayan (1915-1981) was born on the first kibbutz, Degania Alef, to Jewish-Ukrainian parents. He was named after Moshe Barsky, a kibbutznik from Degania who was murdered in an Arab attack. At just 14 years of age, Dayan joined the Haganah defense force. In 1936, he began training with a British military unit headed by his hero, Major General Wingate. During World War II, Dayan was part of a unit that ran covert operations in Nazi-allied Vichy French territory and participated in the Allied invasion of Syria and Lebanon. In one battle, a sniper bullet missed his head, but the resulting shrapnel destroyed his left eye. His eye muscles were ruined, too, so he could not be fitted with a glass eye, and henceforth wore his characteristic black patch. During Israel’s Independence War, Dayan commanded the Jordan Valley units, and was able to stop the Syrian advance. He also led the takeover of towns like Ramle and Lod, and was part of the negotiating team that brought the war to an end. In 1949, Dayan took charge of the Southern Command and worked to secure Israel’s borders. This meant a policy of strong retaliation for Arab attacks, at times brutal. While it brought him a lot of condemnation, Dayan insisted that it was “the only method that proved effective”. In 1953, Ben-Gurion appointed Dayan the new Chief of Staff, and the latter went on to implement Ben-Gurion’s “three-year defence programme” to reorganize the IDF. Among his accomplishments was founding a military academy for high-ranking officers and establishing new intelligence units. In 1955, Dayan and Shimon Peres signed a series of deals with France to strengthen the IDF, leading to the purchase of over 100 jets, 260 tanks, and 300 trucks. In 1956, Dayan led Israel’s operation in the Sinai (jointly with France and England) and proved his military genius. The French later awarded Dayan with a Legion of Honour. After retiring from the IDF, Dayan joined Ben-Gurion’s government as Minister of Agriculture. During the Six-Day War, he took the military reins again as defense minister and oversaw the liberation of Jerusalem. He remained defense minister until the Yom Kippur War, after which he resigned due to what is generally considered to be his greatest failure. He subsequently fell into a deep depression. In 1977, Dayan returned to government as foreign minister and, no longer the hawk he once was, played a key role in the peace treaty with Egypt. Dayan spoke Arabic fluently, and lamented that more Israelis didn’t. He wrote four books and was also an amateur archaeologist, amassing a large collection of antiques which are now at the Israel Museum. In 1981, he founded a new political party, Telem, but passed away shortly after from a heart attack and complications of cancer. The New York Times eulogized him as “a general who made war, a diplomat who made peace.”

Words of the Week

We cannot save each water pipe from explosion or each tree from being uprooted. We cannot prevent the murder of workers in orange groves or of families in their beds. But we can put a very high price on their blood, a price so high that it will no longer be worthwhile for the Arabs, the Arab armies, for the Arab states to pay it.

– Moshe Dayan

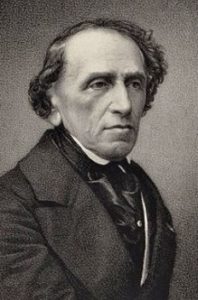

Jacob Liebmann Beer (1791-1864) was born near Berlin, then in the Kingdom of Prussia, to a wealthy, observant Jewish family. His father was the president of Berlin’s Jewish community and ran a large synagogue in his home. His mother received the prestigious Order of Louise from the Prussian queen, and because she was an observant Jew, got a small statue instead of the traditional cross. The Beer children received the best secular education, as well as private tutors in Jewish studies. All three sons became famous: Wilhelm Beer as an astronomer, Michael Beer as writer, and Jacob Beer as a composer. When his beloved grandfather Meyer passed away, Jacob added the name to his own, changing it to Meyerbeer. He also vowed never to abandon the faith of his fathers, while many of his friends “converted” to Christianity to be accepted in society and to take on jobs otherwise barred to them. Meyerbeer was taught music from a young age by some of the best instructors of the time. He performed his first public concert at just age nine. Meyerbeer’s early work involved writing religious music for his father’s synagogue, and his first big production was a ballet-opera called The Fisherman and the Milkman, followed by the musical God and Nature, and the opera Jephtha’s Vow. He wrote beautiful pieces for the piano, clarinet, and full orchestras, and vacillated between composing and playing music himself (which he preferred). Having faced many difficulties in his youth, Meyerbeer founded the Musical Union to support up-and-coming composers. In 1813, he was appointed Court Composer for the Grand Duke of Hesse. Several years later, he felt he had lots more to learn and moved to Italy. There he wrote some of his most renowned operas. By 1824, he had become world-famous, and his 1831 grand opera, Robert le diable, made him the equivalent of a modern-day superstar. The following year, he received the Legion of Honour, the highest award in France. In 1841, he was described as the “German Messiah” who would save the Paris Opera from its death, and shortly after also became director of music for the Prussian royal court. Not surprisingly, his success and wealth drew the ire of his colleagues, and Meyerbeer faced terrible criticism and anti-Semitism (especially from Richard Wagner, once his pupil). Meyerbeer remained graceful nonetheless, and never responded to the attacks on him. He continued to compose popular works until his last day, and has been credited with being “the most frequently performed opera composer” of the 19th century. He inspired the works of later greats like Dvořák, Liszt, and Tchaikovsky. He was also a generous philanthropist, a devoted husband and father to five children, and never broke his vow to die an observant Jew. Meyerbeer remains one of the greatest musicians of all time.

Jacob Liebmann Beer (1791-1864) was born near Berlin, then in the Kingdom of Prussia, to a wealthy, observant Jewish family. His father was the president of Berlin’s Jewish community and ran a large synagogue in his home. His mother received the prestigious Order of Louise from the Prussian queen, and because she was an observant Jew, got a small statue instead of the traditional cross. The Beer children received the best secular education, as well as private tutors in Jewish studies. All three sons became famous: Wilhelm Beer as an astronomer, Michael Beer as writer, and Jacob Beer as a composer. When his beloved grandfather Meyer passed away, Jacob added the name to his own, changing it to Meyerbeer. He also vowed never to abandon the faith of his fathers, while many of his friends “converted” to Christianity to be accepted in society and to take on jobs otherwise barred to them. Meyerbeer was taught music from a young age by some of the best instructors of the time. He performed his first public concert at just age nine. Meyerbeer’s early work involved writing religious music for his father’s synagogue, and his first big production was a ballet-opera called The Fisherman and the Milkman, followed by the musical God and Nature, and the opera Jephtha’s Vow. He wrote beautiful pieces for the piano, clarinet, and full orchestras, and vacillated between composing and playing music himself (which he preferred). Having faced many difficulties in his youth, Meyerbeer founded the Musical Union to support up-and-coming composers. In 1813, he was appointed Court Composer for the Grand Duke of Hesse. Several years later, he felt he had lots more to learn and moved to Italy. There he wrote some of his most renowned operas. By 1824, he had become world-famous, and his 1831 grand opera, Robert le diable, made him the equivalent of a modern-day superstar. The following year, he received the Legion of Honour, the highest award in France. In 1841, he was described as the “German Messiah” who would save the Paris Opera from its death, and shortly after also became director of music for the Prussian royal court. Not surprisingly, his success and wealth drew the ire of his colleagues, and Meyerbeer faced terrible criticism and anti-Semitism (especially from Richard Wagner, once his pupil). Meyerbeer remained graceful nonetheless, and never responded to the attacks on him. He continued to compose popular works until his last day, and has been credited with being “the most frequently performed opera composer” of the 19th century. He inspired the works of later greats like Dvořák, Liszt, and Tchaikovsky. He was also a generous philanthropist, a devoted husband and father to five children, and never broke his vow to die an observant Jew. Meyerbeer remains one of the greatest musicians of all time.