Israel’s First Printers – and Farmers

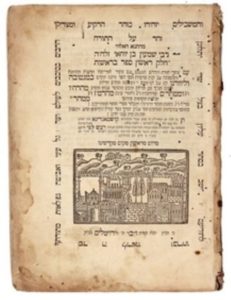

Page from a Zohar printed by Bak in Jerusalem

Israel Bak (1797-1874) was born in Berdichev, Ukraine to a Hasidic family of printers. He took over the business at the age of 18, and over the next seven years printed thirty books. Unfortunately, the family printing press was shut down, and over the next decade Bak unsuccessfully tried to rebuild the business. In 1831, he made aliyah and settled in Tzfat. He established a new printing press, and Jewish books began to be printed in Tzfat again for the first time since the 1600s, when the previous printing press was shut down. Meanwhile, Bak also purchased a plot of land near Mt. Meron and started the first Jewish agricultural colony. Some credit him as being the first modern Jewish farmer in Israel. It was he that inspired (former Jew of the Week) Sir Moses Montefiore to start investing in more Jewish settlement and agricultural development of the Holy Land—a seminal event upon which the later Zionist movement was built. Sadly, Bak lost everything in the Tzfat earthquake of 1837 and the Druze Revolt of 1838. He relocated with his family to Jerusalem, there establishing the holy city’s first-ever printing press. From there he printed 130 books, as well as the second Hebrew newspaper in Israel’s history, Havatzelet.

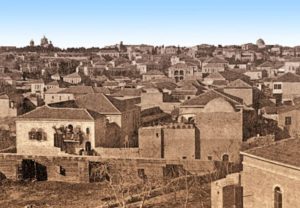

Kirya Ne’emana in 1925

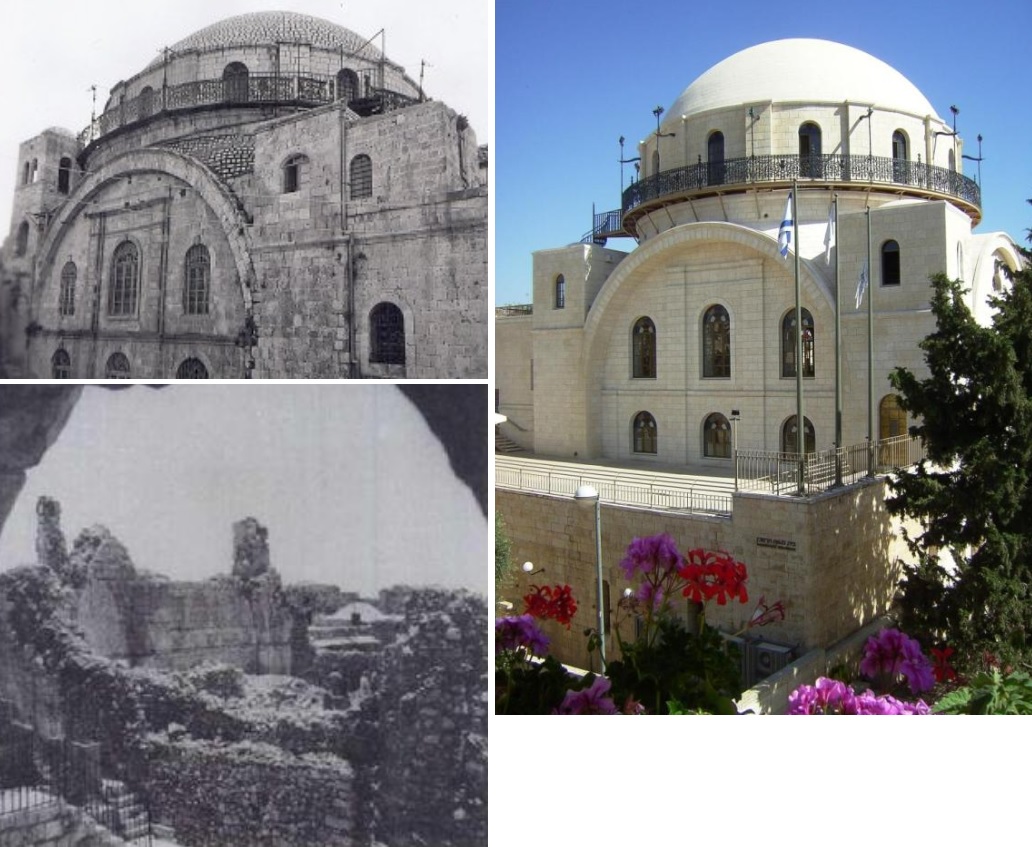

After he passed away, his son Nisan Bak (1815-1889) took over the printing business. Nisan sold the press in 1883, deciding to focus all of his efforts on rebuilding Jewish life in the Holy Land. Back in 1843, he had prevented the Russians from purchasing a coveted plot of land near the Western Wall where they intended to build a church and monastery. He was able to procure vast sums of money (with the help of the Ruzhiner Rebbe) to secure the area for the Jews, and there built the illustrious Tiferet Israel Synagogue (also known as Beit Knesset Nisan Bak, and the Hurva, “Ruin”, because it was destroyed by the Arabs in Israel’s War of Independence in 1948, before being rebuilt and reopened in 2010). In 1875, Bak founded one of the first modern Jewish towns in Israel, just outside Jerusalem’s walls, called Kirya Ne’emana. He built 30 homes for the Hasidic community, and distributed the remaining plots to large numbers of Iraqi, Syrian, and Persian Jews. In 1884, he co-founded (with his brother-in-law, Israel Dov Frumkin) the Ezrat Niddahim Society to stop Christian missionaries from targeting Jews. The society also established a Yemenite Jewish quarter in Jerusalem, and raised funds to support and educate Jerusalem’s impoverished.

Top left: the Hurva Synagogue in 1930; bottom left: the ruins in 1967; right: the Hurva today (photo credit: Chesdovi). Sir Moses Montefiore paid for much of the early construction. More than half of the money came from the wealthy Iraqi-Jewish family of Ezekiel Reuben. The synagogue was completed in 1864 and originally called Beit Yakov in honour of Edmond James (Yakov) de Rothschild. It was considered the most beautiful building in Jerusalem, and nicknamed “the glory of the Old City”.

Words of the Week

I see Israel, and never mind saying it, as one of the great outposts of democracy in the world, and a marvelous example of what can be done, how desert land almost can be transformed into an oasis of brotherhood and democracy. Peace for Israel means security and that security must be a reality.

– Martin Luther King, Jr.

Mordechai Martin Buber (1878-1965) was born in Vienna to a religious Jewish family. His parents got divorced when he was just three years old, so Buber was raised in what was then Poland by his grandfather. Despite growing up in a richly Hasidic home, Buber began reading secular literature and returned to Vienna as a young man to study philosophy. Around the same time, he became active in the Zionist movement and soon became the editor of Die Welt, the main newspaper of Zionism. It wasn’t long before Buber became dissatisfied with the secularism and “busyness” of Zionism and returned (partially) to his Hasidic roots. He saw in Hasidic communities the right model for a new Israel, and a better alternative to the entirely-secular kibbutz. Buber ultimately saw Zionism not as a nationalist or political movement, but as a religious movement that should, first and foremost, serve to spiritually enrich the Jewish people—along with the rest of the world. He would later be credited with being the father of “Hebrew humanism” and “spiritual Zionism”. In 1908, he was invited to address a group of Jewish intellectuals known as the “Prague Circle”, and to “remind them about their Judaism”, as the group’s leader had requested. Among the members of the Circle was (former Jew of the Week)

Mordechai Martin Buber (1878-1965) was born in Vienna to a religious Jewish family. His parents got divorced when he was just three years old, so Buber was raised in what was then Poland by his grandfather. Despite growing up in a richly Hasidic home, Buber began reading secular literature and returned to Vienna as a young man to study philosophy. Around the same time, he became active in the Zionist movement and soon became the editor of Die Welt, the main newspaper of Zionism. It wasn’t long before Buber became dissatisfied with the secularism and “busyness” of Zionism and returned (partially) to his Hasidic roots. He saw in Hasidic communities the right model for a new Israel, and a better alternative to the entirely-secular kibbutz. Buber ultimately saw Zionism not as a nationalist or political movement, but as a religious movement that should, first and foremost, serve to spiritually enrich the Jewish people—along with the rest of the world. He would later be credited with being the father of “Hebrew humanism” and “spiritual Zionism”. In 1908, he was invited to address a group of Jewish intellectuals known as the “Prague Circle”, and to “remind them about their Judaism”, as the group’s leader had requested. Among the members of the Circle was (former Jew of the Week)