The Man Who Made the Citroën Car and Helped Win World War I

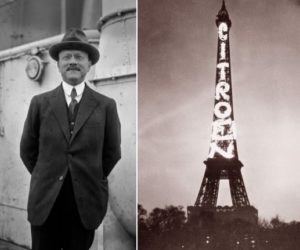

As a child, André Citroën was inspired by the Eiffel Tower. He lived to see his name displayed on it. This early “billboard” marketing technique is still a Guinness World Record for largest advertising sign.

André-Gustave Citroën (1878-1935) was born in Paris to a Dutch-Jewish father and Polish-Jewish mother. The last name “Citroën” comes from his grandfather, who sold fruit for a living in the Netherlands and was known as Limoenman, so his son made the family last name Citroen, which means “lemon”. As a child, Citroën was inspired by the Eiffel Tower and by the works of Jules Verne and dreamed of becoming an engineer. After graduating with an engineering degree, Citroën went on a trip to Poland to see his mother’s birthplace. There, he saw a carpenter working with a gear that had a “fish bone” structure. Citroën realized that such gears could be used in automobiles to make them quieter and more efficient. He bought the patent from the carpenter, then tweaked the designs until he came up with the automotive double helical gear. The Mors auto company successfully integrated these gears to make better cars, and by 1906 Citroën was the company’s director. With the outbreak of World War I, factories were being converted to produce weapons, and Citroën soon became world-renowned for increasing factory productivity. He took charge of fellow car-maker Renault’s large plant, now having its 35,000 employees making armaments. Citroën’s work played a key role in ensuring the Allies were well-armed and helping them win the war. Following the war, Citroën founded his own Citroën automobile company in 1919. Within just a dozen years, it became the world’s fourth largest car manufacturer. The company was most famous for its executive Traction Avant model, which pioneered a number of revolutionary features including independent suspensions on all four wheels and front-wheel drive. Investing so much money into research and development ultimately drove the company to bankruptcy and it was bought out by its tire maker Michelin. Citroën died the following year from cancer. He was buried in Paris’ famous Montparnasse Cemetery, with a traditional Jewish ceremony presided by Paris’ chief rabbi. A number of streets and parks in the city are named after him, and in 1998 Citroën was inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame. Meanwhile, his company retained his original vision, and continued to pioneer many new technologies (like modern disc brakes, self-leveling suspensions, and swiveling headlights), becoming one of the most iconic car brands in the world.

Should You Wear a Red String On Your Wrist?

Words of the Week

If someone says,“I have worked hard, and I have not been successful,” don’t believe him. If someone says,“I have not worked hard and I have been successful,” don’t believe him. If someone says,“I have worked hard and I have been successful,” believe him!

– Talmud (Megillah 6b)

The double helical gear inspired the Citroën logo.