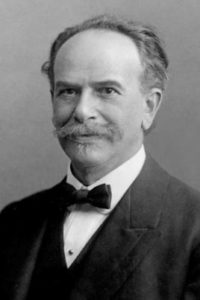

Father of American Anthropology

Franz Boas (1858-1942) was born in Germany, the son of Jews who had left their Orthodox upbringing and raised their children in a very liberal environment. Boas studied physics, geography, and mathematics at a number of prestigious German universities. Although his first Ph.D was in physics, Boas was more fond of geography. In 1883, he went on an expedition to Baffin Island to live among the Inuits. He soon realized that the prevailing European notion of aboriginals as uncivilized “savages” was wrong, and concluded that “we ‘highly educated people’ are much worse, relatively speaking”. From there, Boas continued his studies of non-European cultures, working from Berlin’s Royal Ethnological Museum. He came to the conclusion (unpopular at the time) that all human beings and all cultures were equal. Ironically, he was a victim of rising anti-Semitism, and was constantly prodded to convert to Christianity in order to be accepted in German society. Boas moved to the United States and became the assistant editor of the journal Science. Two years later, he was appointed head of Clark University’s new department of anthropology, and in 1896, began lecturing at Columbia University as well. He soon developed a Ph.D program in anthropology – the first in America – and cofounded the American Anthropological Association. His students would go on to found more Ph.D programs in universities across America. Not surprisingly, Boas is often referred to as the “father of American anthropology”. Over the years, Boas played a central role in developing the science of anthropology. His 1911 The Mind of Primitive Man was the major textbook on the subject for years, and his writings heavily influenced just about every branch of anthropology. Meanwhile, Boas was a vocal opponent of racism, eugenics, cultural evolution, and social Darwinism, and it has been said that he “did more to combat race prejudice than any other person in history.” During the Nazi era, Boas worked tirelessly to help German and Jewish scientists escape Europe, and assisted many of them in finding positions in America. He was also editor of The Journal of American Folklore, founded the International Journal of American Linguistics, served as president of the New York Academy of Sciences, as well as president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. By the time of his death he was among the most well-known, influential, and respected scientists in the world.

Words of the Week

The righteous do not complain about wickedness, but increase righteousness. They do not complain about heresy, but increase faith.

– Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook