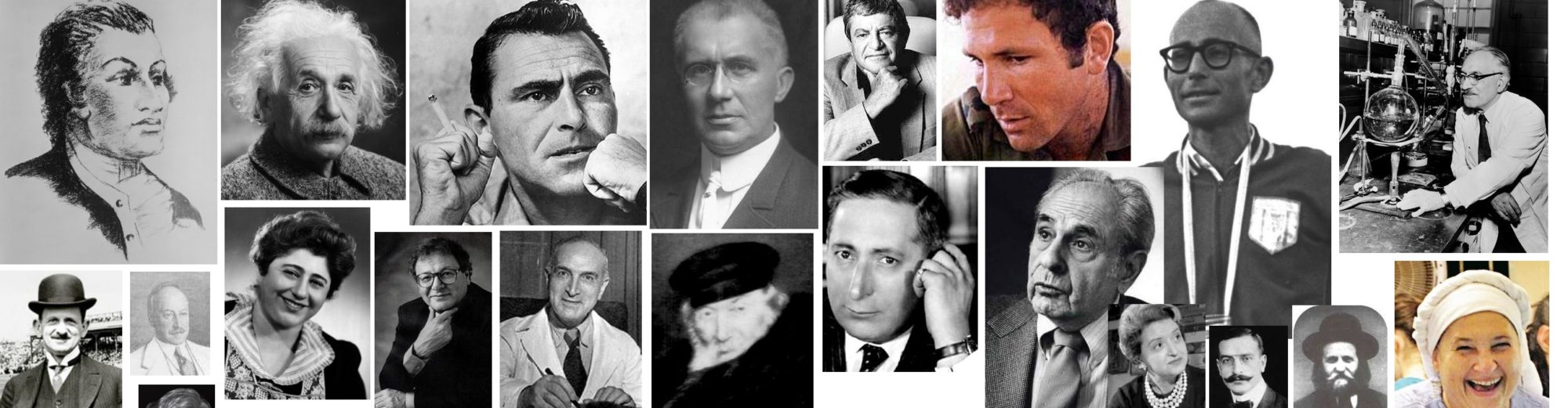

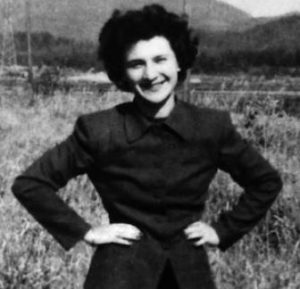

The Woman Who Wrote Japan’s Constitution

Beate Sirota Gordon helped draft the Japanese constitution, and transformed Japanese society, when she was just 22 years old.

Beate Sirota (1923-2012) was born in Vienna, the daughter of Russian-Ukrainian Jewish immigrants. When she was five years old, her father, a popular musician, accepted a position to teach music at what is now the Tokyo University of the Arts. The family moved to Japan, where Sirota studied in German and American schools. At 16, she went to college in California and got a degree in languages, speaking English, German, French, Russian, and Japanese fluently. When World War II broke out, Sirota was one of just a handful of (non-Japanese) people in America who could speak Japanese, and went to work for the Office of War Information. Her main job was to monitor Japanese radio signals and translate their broadcasts. During this time, she had no contact with her parents who were still living in Japan. As soon as the war ended she volunteered to go to Japan as a US Army translator, hoping to find her parents (she did). She would become the first civilian woman admitted to the country. In 1946, the Americans started working on a new constitution for Japan and Sirota (the only woman on the committee) was tasked with writing the section on civil rights. She made it a priority to ensure that Japanese society would finally allow equality for all, especially better conditions for women who still had no rights in the country. Sirota personally drafted Article 14 (“All of the people are equal under the law and there shall be no discrimination in political, economic or social relations because of race, creed, sex, social status or family origin…”) and Article 24 (“Marriage shall be based only on the mutual consent of both sexes and it shall be maintained through mutual cooperation with the equal rights of husband and wife…”) Despite reservations from both the Japanese and American negotiators (who felt she was giving Japanese women more rights than even American woman had), Sirota eventually convinced her counterparts to include the clauses. She is therefore credited with being the central force for bringing social equality and women’s rights to Japan.

During her time working on the constitution, Sirota met her future husband, Lt. Joseph Gordon. They returned to the US and settled in New York. After briefly working for TIME magazine, Sirota pursed her passion for art, music, and dance. Meanwhile, she worked at the Japan Society helping Japanese students and immigrants (one of whom was Yoko Ono). Sirota played a large role in introducing Japanese (and Asian) music and art to the West. By 1970, she was Director of Performing Arts for the Asia Society, and began to travel all over Asia to remote communities in search of traditional art forms. She would then invite these artists on tours to the West. All in all, Sirota organized 39 tours in 16 countries. In the US alone, her shows were seen by 1.5 million people in 400 cities. She also made five films and multiple television programs about Asian art, and recorded 8 albums of music. For all of her tremendous work, Sirota received dozens of awards, including the prestigious Order of the Sacred Treasure from the Japanese government. In Japan, two films have been made about her life. In 1995, Sirota published a memoir in Japanese, followed by an English version in 1998, titled The Only Woman in the Room. Today, she is one of Japanese greatest feminist icons.

In Memory of Lori Kaye, 60, “Who Thought of Others Before Herself”

Words of the Week

Until now you have focused on what you need from God; it’s about time you asked, “What is needed of me?”

– Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi (1745-1813)