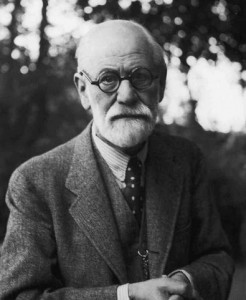

The Father of Psychoanalysis

Sigismund Schlomo Freud (1856-1939) was born in what is today the Czech Republic to Galician-Jewish parents. His father, a once-Hasidic wool merchant, brought the family to Vienna where Freud grew up. A natural academic, he absorbed his studies effortlessly and became proficient in 8 languages. His favourite were the works of Shakespeare, which he read his entire life and are said to have greatly influenced his theories. He became a doctor and worked for several years in hospitals, asylums, and clinics before starting his own practice specializing in nervous disorders. At the same time, he married the daughter of Hamburg’s chief rabbi and they would go on to have 6 kids. After learning hypnosis in Paris, Freud found that a certain patient was able to open up to him while hypnotized and in the process of talking out her problems, brought about her own relief. Freud realized that patients need only be guided to speak freely, with no need for hypnosis. He also found that much of their issues were reflected in their dreams. By 1896, he abandoned hypnosis entirely and created “psychoanalysis”. From his own experiences and that of his patients, he put together a series of new theories about the mind, emotions, consciousness, religion, dreams, and sexuality. He published a range of books and papers, and delivered lectures each Saturday night. On Wednesdays, he led a small discussion group with 5 other physicians, all Jews. The Wednesday Psychological Society would evolve into the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society, and spawn many other such groups across Europe and the world. Freud would go down in history as the founding father of psychoanalysis. His ideas inspired a proliferation of new literature in psychology, philosophy, science, and sociology. Despite the rise of the Nazis and the burning of his books, Freud was determined to stay in Austria until he was finally convinced by colleagues that his life was in danger. After much difficulty, he escaped to London (though 4 of his older sisters could not, and perished in the Holocaust). He continued his work, analyzing patients and writing more of his ground-breaking ideas. After battling an oral cancer for nearly two decades – a direct result of his smoking addiction – he reached a critical state of illness and a decision was made together with doctors and Freud’s daughter to end his life. After several days of high-morphine doses, Freud passed away on Yom Kippur.

Words of the Week

Someone else’s material needs are my spiritual responsibility.

– Rabbi Israel Salanter